When I worked in a particularly bad office environment, I remember going to therapy and talking to my therapist about how bad it was to work there. I expected to be told that I needed to re-evaluate my existence or try and think around the situation, but my therapist mostly told me that the job sucked and that I was depressed because it was bad. I had no real way to leave, and thus therapy became a form of venting. I’d talk about how bad it was, I’d get suggestions about ways to minimize the bad, but there was no real way of dealing with the problems other than removing myself from them.

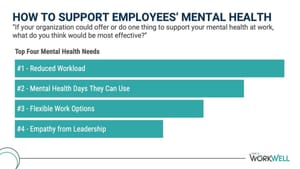

Thematically, Dave Whiteside of YMCA WorkWell posted a study of 2000 working adults, asking them what their organizations could do to improve their mental health in the workplace.

Note how there is no mention of wellness, meditation, “team cohesion,” or “being close to my colleagues.” There is nothing about office culture, teamwork, “collaboration,” or “feeling like I belong to the organization.” Respondents were asked to fill in their answers rather than select from pre-approved ones, meaning that these were, for all intents and purposes, what people actually thought versus having to choose from a selection of answers.

In short, the biggest mental health issues caused by a company appear to be from working there.

This is part of an ongoing battle that companies are having with their workers and the world at large - they are trying to make things like “mental health” and “employee engagement” these deeply complex and multi-faceted issues that can only be solved through an even more complex series of corporate policies. It’s a similar conversation to the one I’ve had before about company loyalty - that the actual solutions to the problems that most workers face are simple in practice but difficult at scale because they involve a level of industrial introspection that most companies don’t want to engage in.

If you want loyal workers, you pay and treat them well while also making their job as easy to perform as possible. This involves (but is not limited to) making sure that their tasks are clearly-set, that they are managed by people that know how to manage, and that any difficulties they face are met with an attempt at reconciliation rather than immediate damnation. When someone is loyal, it’s because they feel like the company gives a shit about them and that they’re getting a fair deal in working for them (as this is a transaction of labor for money).

Furthermore, they feel a degree of kinship and respect for their leadership, something that’s earned through executives that actually do stuff and communicate with their workers. Their managers are people that show them respect, and get them what they need, all while helping them deal with the adversity that comes from any kind of labor.

As many of you will likely note, this is not how most management or leadership generally manifests. Many (most?) managers are disconnected from both the worker and the work product, seeing themselves as slave drivers rather than navigators. Most leaders are entirely divorced from the work that enriches them and find it deeply troubling when they’re called upon to actually do anything. Those making the orders are rarely the ones carrying them out, leaving workers almost entirely at the mercy of what is promised to clients or shareholders. At the same time, management and leadership constantly calls upon said workers to “be loyal to” and “appreciate what they’ve got at” the company they’re working for.

When workers face mental health issues due to this flawed, failed chain of command, they are told that their company cares about their mental health because somebody read about it in Entrepreneur or Fortune Magazine. “Wellness” and “mental health” have become corporate buzzwords used to escape actual responsibility for working conditions, effectively passing the blame for the damage that a toxic culture has done to the worker’s mental health…right back to the worker.

Once you make something a “mental health problem,” it isolates the worker and turns their pain into an individual problem. Those who are not facing (or volunteering that they’re facing) mental health issues at work are used as indicators that nothing is wrong and that any problems with mental health are isolated cases that can be dealt with by policy.

It is, in short, an attempt to totally shirk responsibility for working conditions. It’s significantly easier to offer everybody access to a meditation app or occasionally offer “mental health days” than it is to do a comprehensive audit of your workers. Said audit needs to be handled by a third party, and you actually have to want to know the answers (versus doing it to have the appearance of caring) and take action based on them.

Industrial Despair

I have a working theory that there are many, many corporations that simply do not know who is doing what and how much their contribution actually is. As a result, there are many people that do a great deal of work while being made to feel as if they’re totally unappreciated, all while watching people who do less (or no) work get accolades or promotions for their “team’s performance.”

On top of this, I believe a great many people have accepted that some level of bullying, cliques and top-down punishment - the culmination of years of older people telling us that we “have to prove ourselves” and to suck it up when faced with distant or actively malicious management. Elder generations have lionized suffering as a necessary part of labor - a belief that very rarely survives the simple test of asking “how exactly did that help you?” - and that earning bigger paychecks and better treatment is done only through suffering, because “that’s what makes you better.”

I will tell you, from a personal perspective, that the suffering - the out-and-out bullying, the antagonism from both the executive and managerial level, the sense of drowning because I was left untrained yet screamed at for not performing - did nothing to make me better. I am a success now, and I’m proud of what I’ve done, but none of that success was borne from being treated poorly. Having managers claim my work as their own did not make me want to work harder, nor did it teach me anything about management other than how not to do it. Being held late on holiday weekends because my boss wanted to change three agenda points and have us in the office to confirm he liked them made me feel scared and trapped, but it did not make me better at anything.

In the rare cases where I’ve had good management, I’ve remembered them and stayed fiercely loyal to them, even to this day. I speak regularly of Will Porter, my editor at PC Zone, a man who did not go easy on me with critiques but also actively sought to frame them as “you can be better” rather than “you are bad,” someone who acted as a mentor, an ally and a leader. Jeff Lovari has remained a friend and a mentor for 14 years, and I still remember him introducing me to my first working contact at Investor’s Business Daily - and how often he’d coach me through extremely trying times.

I will also admit I carry grudges on a somewhat permanent basis, which is why I’ll never name nor be particularly specific about any bad manager I’ve had. But I remember each and every one of them, along with everything I had done to me and watched be done to everybody else. I heard similar stories from people my age, and frowned as older people told us “that’s just the way things are” as we relayed multiple stories of bosses screaming at freshly-graduated college students. I became a much darker, more insular person when I worked for bad bosses, constantly afraid of everything because I had been taught to be in the workplace.

At some point, this shit has to stop.

There is no valor in suffering for a salary. The “thick skin” that people think you grow from being abused is trauma, and it doesn’t make you stronger - in fact, I’d argue it makes you more likely to traumatize others, kind of like having a bad parent or relationship. The noxious (and false) belief about young people being “snowflakes” suggests only that elder generations believe that a little bit of trauma is good for you. In their eyes, being overworked, exploited and abuse makes you “stronger,” yet it’s hard to get anyone to articulate how or why this is the case.

The best mental health support a company can give their workers is to make their lives easier and to remove toxicity from the workplace. Bad managers, bad working conditions, and too much work are why people experience mental health problems in the workplace, not their mindset or perspective on the company. There is no amount of talking that will fix a poorly-managed workplace, and “mindfulness” or “wellness” or “employee engagement” are just condescending, offensive ways to escape blame.