The Wall Street Journal is on a roll, with an incredible piece of scare-journalism about how Gen Z may never work in an office - and how that’s scary, bad, and harmful.

Working from home can make anyone lonely and anxious, but experts say these effects are more pronounced for Gen Zers—who have spent a lot of time on screens from the start. “This is the cohort with the least amount of person-to-person interaction while growing up,” says Dr. Nishizaki, adjunct professor at California State University, Los Angeles. “There is a link there between depression and anxiety and how we constantly compare ourselves to other people, and then we are only seeing our best selves online and on social media.”

Compounding the problem, young adulthood, from ages 18 to 29, is a particularly lonely time of life for many, with or without screens, says Jeffrey Arnett, a professor of psychology at Clark University.

It is “the time when people spend the most time alone until you get to your 70s,” says Dr. Arnett. “You may not have a romantic partner, you may not see your parents so much anymore because you probably don’t live at home, and you change residences so much that that complicates having stable friendships.”

So, you may think I’m going to eviscerate this line-by-line, and I may indeed do so, but I want to discuss how many leaps of logic are being made here. First and foremost, the “18-29 is your loneliest time” is one of the more bizarre statements I’ve seen in a newspaper - how in the world did you verify that? Where did this logic come from? Because kids go to college? Then leave college? Anyway, let’s see where the Journal’s imagination takes us next:

That means young remote workers may miss out not only on professional relationships but also on friends and potential romantic partners, says Johnny C. Taylor Jr., president and chief executive of the Society for Human Resource Management.

“There’s something that happens when a group of us, say, ‘Hey, after work on Friday, we’re all going to X bar,’ and you go with a group, and there’s that dynamic,” he says.

I’ve gone over this before, but it is incredible how many people have become dependent on the office for their social interactions, and even more incredible how many people seem to believe this legitimizes a return to the office. It’s also truly stunning that the head of the association of HR professionals would suggest a bad thing about the office is that people aren’t meeting romantic partners or drinking.

I will concede that if you stay at home on the computer all day and do not go out of the house, you will be lonely. However, you are also fully capable of going to an office full of people and being lonely too, because being in a room with people does not automatically mean that they accept you, and can regularly mean that they exclude you if you’re not like them. Why does this consideration never factor into these articles?

That’s right, because there’s an agenda!

Young workers often express concerns about the ability to build a professional network, says Mr. Taylor. This is a problem for any remote worker—but a bigger one for younger people who haven’t established themselves professionally.

“One day, one of their classmates is going to be the CEO of something or the board member of some company, and you won’t have that real authentic relationship with him or her,” says Mr. Taylor.

Remote work may also lead to career crises. Because young millennial and Gen Z workers generally have less experience and less power at work than other age groups, they often worry about whether they are on the right track. They are more likely to be affected by feeling out of the loop, say Drs. Nishizaki and DellaNeve.

Alright, everybody stop what you’re doing and listen, I’m about to tell you a story.

Most of my career in journalism was remote, and this was back in the mid-2000s. I started off with an internship at a magazine and then used that internship to grab as much work as possible until they offered to pay me for it. When they did that, I only physically had to be in the office to take screenshots of a game, and if I was able to do that at home (say, if I was reviewing a game on PC that had a screenshot button). I then got freelance work from another magazine (PC Zone) that I did completely remotely. For years.

Despite that - and perhaps this is a little too personal - I struggled to make friends, even though I was surrounded by people at University. I became closer with my editor Will than I did any friend I made at school, and this was entirely via email and the occasional phone calls. When I went to Penn State, I didn’t make many if any friends from my actual classes - I made them through people in my dorms, along with clubs and societies I joined. In the offices I worked at, I’ve made one close friend, and most of that came from us being trapped in a truly awful professional situation that was vastly compounded by physical presence in an office.

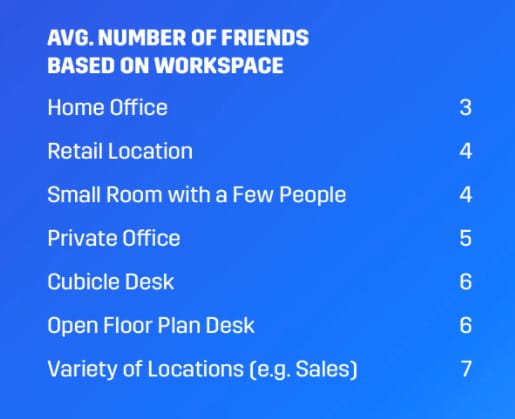

What I am not saying is that everyone has the shared experience, or that nobody has ever made a friend through work. My point is that the assumption that physical presence in an office is a guarantor of a better social life. As with many of my informal, unscientific surveys, I found that about half of my replies made zero friends from the office, and the other half made a few. Much of the research I’ve found suggests that having a friend at work is a net positive, but I can’t find anything that actually discusses how these friendships are started - only that the number of friends - which includes but isn’t limited to “close” friends” - seems to increase based on the size of the company, which makes sense.

What is interesting is this research from Olivet Nazarene University:

While it’s clear someone might report having more friends in an office, it’s very clear that the trope of “you won’t make any friends working from home!” doesn’t seem to be the case. Furthermore, the term “friends” unhelpfully seems to be a combined cluster of multiple different kinds of terms for a friend - “real” friend, just-at-work friend, best friend, and so on - but seems to suggest that those working from home are not ostracized, desperate pariahs.

Network Effects

Another frustrating part of the Journal article is their adherence to another assumption - that the office is great for networking, and remote work is bad for it. Dipping back into my history, and how my company has run for years, I have done almost the entirety of my networking online. Outside of my yearly CES trip, I’ve gone to perhaps three industry events to “network” and mostly found myself wishing I was at home.

I’m also sick and tired of charlatans claiming that you can’t make “real, authentic relationships” digitally.

Young workers often express concerns about the ability to build a professional network, says Mr. Taylor. This is a problem for any remote worker—but a bigger one for younger people who haven’t established themselves professionally.

Wanna know how I got my professional network in 2009? The internet. The god damn internet. It is here, it has been here, it worked then and it worked now. I went and got coffee with people that I emailed. I went and got drinks with people I tweeted at. My closest friends? The internet. My watch? The internet. My beautiful wife? The internet. All of this is completely possible if you know how to use a computer, which Gen Z has been proven to do.

The actual roadblocks to doing this remotely are people writing in major newspapers fatalistically claiming that young people’s careers are on the rocks because they’re working remotely. The actual roadblocks are exclusionary, thoughtless executives and managers that seek to keep young people from exposure to valuable clients, or the push to get people back in the office so that old white guys can sustain their hegemony and feel powerful. The other roadblocks are companies that don’t invest in fostering the talent of young people - a subject I’ve written about too many times - which is something they haven’t done in the office and are definitely not doing in a remote work setting. Take this wonderful quote:

Remote work may also lead to career crises. Because young millennial and Gen Z workers generally have less experience and less power at work than other age groups, they often worry about whether they are on the right track. They are more likely to be affected by feeling out of the loop, say Drs. Nishizaki and DellaNeve.

…

“It can just feel like some weird videogame sometimes where it’s all on your computer and none of these people exist,” says Francis Zierer, 27, who works in marketing at a software company in New York. At home, like many young workers who started new jobs remotely during the pandemic, he has experienced a degree of “FOMO,” or fear of missing out.

Man, if only a manager or supervisor had some sort of power to talk to the people they managed or supervised. They’re the ones who can change this after all!

The concern young workers share about being forgotten isn’t unfounded, says Mr. Taylor of the Society for Human Resource Management. The organization conducted a survey in 2021 that revealed 42% of supervisors say they sometimes forget about remote workers when assigning tasks.

“If I’m the supervisor and I have a really juicy assignment, I give it to the person who I just passed in the hallway, because this concept of out of sight, out of mind applies in human nature,” says Mr. Taylor. “So you are missing out on some key opportunities to showcase your talent.”

I am so sick and god damn tired of this I could scream. For once I want one of these writers to follow up a quote like that with a question such as “well, what are they going to do about it? Is that a foregone conclusion? Surely that’s a fairly of the manager?” or any of the most blatantly obvious questions in the world. It’s also truly ghoulish - though not unexpected - that an “HR Expert” at the top of the HR society would be pushing for pro-management messaging.

In any case, the problem with young people’s careers isn’t remote work - it’s the people they work for. If you are a manager that is giving an assignment to the person you last saw in the hallway rather than the person who can do it the best, you are a scumbag. The person in question that’s also ignoring someone who’s remote is likely ignoring someone because of the color of their skin, or their gender, or something else they don’t like - they are biased, lazy, and cretinous.

And yet we keep seeing these bizarre and baseless takes about how “remote work fails young people” based on the vague assumptions of people that live on an island, or the head of an HR association, or another god damn professor:

Tsedal Neeley, a Harvard Business School professor and author of a book on remote work, believes companies should take on the responsibility of engaging their younger employees, especially in remote-work environments.

“Young people who are building their careers and who are less established in their careers are longing for some form of immersion,” she says.

Without a sense of connection and belonging, they are less likely to feel attached to their employers, she says. “They are going to be quick to want to leave if they don’t feel fully connected and if they don’t like the culture they see.” More than half of Americans planned to look for a new job within the year, according to a Bankrate survey of more than 2,000 workers in July 2021. Among those surveyed, twice as many Gen Z workers as baby boomers and Gen X workers said they were likely to start the search.

You wanna know what actually keeps people at a company? Paying and treating them well. People like Professor Neeley want to turn employee engagement into alchemy so that they can sustain their careers, and journalists simply accept what they say because they have a title. There is no analysis here - no consideration of the facts, no introspection, just mindless nodding as a head of a professional services association and a professor confirm every bias of every executive that’s ever read the Wall Street Journal.

Every time they quote a professor or HR professional, they say remote work is bad for the worker, and the worker doesn’t like it and feels bad. Every time the article quotes a worker, the worker says that they like remote work and prefer it to the office. Remote work has proven itself, again and again, to be more productive and by and large better for most people, and the only people that seem to violently disagree with it are managers, professors, and executives - people who are, by definition, disconnected from the process of the work that enriches them.

It’s A Job, Not A Debt

Last week, the Journal proved this with probably the funniest piece I’ve read on remote work titled “Sorry, Bosses: Workers Are Just Not That Into You.” It is a sprawling piece focused on one almighty doofus, the CEO of a sports marketing firm that installed a scoreboard, a tunnel between the elevator and the lobby (to mimic going into an arena), free beer, and, for whatever reason, a historic race car.

The article mostly follows executive John Rowady’s descent into madness:

Nevertheless, much of the team prefers to work remotely most days, Mr. Rowady says, even if it means gazing at the family minivan in the driveway instead of a Formula One speed machine.

“It can be frustrating to really do everything that you could possibly do, try not to be overbearing, engage with your employees—and then have to deal with situations where people still aren’t comfortable coming back,” he says.

Huh, I wonder why?

Call it the professional version of “It’s not you; it’s me.”

That can be a tough message to accept. Aaron Johnson, president of Automatic Payroll Systems in Shreveport, La., maintains people work best together, and for the past six months he has expected most of his 165 employees to report to the office at least a few days a week. Last year 30% of his staff turned over—twice the typical rate. Many job-hopped to firms based in California, Texas and New York, collecting hefty raises while staying in lower-cost Louisiana and working from home.

What stings, Mr. Johnson says, is that his company trained a lot of those workers and retained them when the economy was at its worst, in 2020. Yet the investment in his people didn’t seem to matter when it was time to reopen the office.

“The amount of effort and energy that was put into ensuring nobody lost their job—that we made the proper adjustments to weather the storm—people just don’t remember those things,” he says. “You have that lack of loyalty.”

I want to be clear that the relationship that Mr. Rowady had with the people that quit his company was that he paid them money to do a job and tolerate whatever working conditions there were, and in return, they did the job. When they decided that they wanted to, they took a similar offer from another company (this is known as “employment”) in which they agreed to also do a job in which they were compensated based on the conditions of said job and the tasks they had to complete.

What Mr. Rowady appears to have wanted was some sort of marriage or slavery situation.

Nobody took advantage of anyone in this scenario. The job of a company is to get people who are talented and train them to do anything they can’t do already. The reason they do this is so that the person is better at something so that they can do better at the job they are paid to do. This is known as “investing in talent,” because you are investing money to make more money, or to make money more efficiently. Mr. Rowady’s reaction isn’t just unreasonable, it’s abusive - it suggests that a worker “owes” their boss something for the boss investing in ways to make the boss more money. You do not deserve a ticker-tape parade for not arbitrarily laying people off during a pandemic - it’s your duty as an executive to make sure that you protect your workers, because they are how you make money - and you definitely shouldn’t expect them to come into the office as some sort of thank you for doing so.

Here’s an idea: if you really want everybody back in the office so badly, fucking pay them. If you are so attached to the idea that someone has to be physically somewhere, compensate them - you are making them do something inefficient and wasteful, so you should have to spend money for the pleasure. On the subject of inefficient and wasteful things, why would you expect a positive reaction to putting a race car in your office? Or a tunnel? All I can think of is how much it cost - I’m going to guess at least $100,000 for the car - and how much of that money could have been spent on…anything else?

What’s worse is this article doesn’t treat Mr. Rowady as a clown - if anything, it supports him:

What is holding up the return to the office right now? Plenty of workers simply don’t feel like it. They’re dining at restaurants, going to movies and taking trips, but offices aren’t on their itinerary. That is delivering a reality check for bosses, who’ve been hoping the plunge in Covid-19 cases meant workers would finally—finally!—come back.

I would like to suggest the Journal adds a “citation needed” here, because so much of this doesn’t make sense. Are they doing this during work? Or after work? And more importantly, who cares? Why are workers being framed as work-shy spongers, and why is the guy who spent six figures on turning his office into a sports museum being framed as a victim?

And why didn’t you try and speak to an employee?

What’s happening here is that Mr. Rowady is disconnected. As ever, it’s always worth turning to the Glassdoor of the subject of an article, where you’ll find stories of massive turnover and “invisible leadership,” leadership that doesn’t care about your growth where it’s “every man for himself, [where you’re] constantly asked to save on budget [and the] CEO loves a good consultant and would rather pay [them] than listen to the people who work for him.”

Mr. Rowady, I think your problem might be that you’re a huge prick!

Even the fake reviews can’t hide one from 2021 that describes rEvolution as having “shady business tactics.”

Breaking The Chain

Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky famously discussed the concept of manufacturing consent - subtle propaganda that exists to support an existing system that’s under attack - and I have tried to avoid thinking in these terms for fear of being too paranoid. But it’s hard not to when I see the mayor of New York City telling people that they “can’t work from home in their pajamas” and blaming accountants not going to their offices (?) for dry cleaners not having work, and even harder when I see article after article fighting this endless battle.

However, one thing I haven’t specifically said is what I think they want.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis in 2008 when I moved to America, I remember everybody - especially bosses - talking about the workforce being “grateful” for the opportunity to work. The great recession created a culture of paid servitude in a climate that had proven that the government was ready and able to bail out companies that weren’t run well enough to survive, but had little support for the regular person. In a grim way, this period established exactly how much power businesses had over people - both the power to control their livelihoods and the protection of the government when times were tough. The Affordable Care Act seemed as if it would be a measure to separate us from our jobs - taking healthcare out of the hands of employers - except that part never quite materialized.

We were at their mercy. And I’d argue that executives got used to it - labor was subordinate to industry, and the workers knew their place.

The pandemic was different, and those who could work remotely got a glimpse of something they hadn’t seen with their employers before - compromise. People were absolutely grateful for the work, as well as the ability to make an income without being exposed to the virus, and bosses agreed…until vaccines and boosters arrived. While we may have moved for a job in 2008 because they were so scarce, and perhaps they’re still scarce today, there was at least a quasi-logic to it - we had to go back, because that’s where they kept the work.

This time, workers are being asked to do something for no reason. While workers felt subordinate to capital, those being asked to return to the office after successfully working from home were being asked to pledge themselves to the company. While workers had entered into what they believed was an exchange of labor for money, companies had grown accustomed to “owning” people for a set amount of time in a week - and without the office, they threw a tantrum.

And this tantrum is manifesting in the form of vacuous articles full of insufferable, mewling executives. Instead of facing that there may be a different and better way of doing things - as executives continually expect their workers to - they are screaming that “you need the office” as their workers continually prove that they don’t.

The reason you’re seeing government figures back these spurious arguments is that it’s significantly easier to gaslight and insult remote workers than it is to accept that there are going to be businesses that suffer if people don’t go back to the office. It is true that stores that were profitable based on the existence of office workers will face hard times, but it’s so painfully obvious that this isn’t about “low-income workers. What it’s really about is the capital forces that own the service businesses around offices, along with the powerful real estate moguls that are terrified they won’t be able to sell their expensive leases.

And these forces are extremely good at influencing the media. That’s why you’re seeing the messaging consistently change, from “the office is better than remote work,” to “young people are ruining office culture,” to “remote work is ruining young people’s lives.” They are doing all they can to disenfranchise those who work from home so that they can continue to retain their power.

At the root of almost every part of this argument is denial. Executives don’t want to admit that they truly don’t understand their company, so they say and do whatever they can to undermine anything that makes them feel self-conscious. Eric Adams is in denial that New York City - as with any global financial hub - has to adapt to a partially-remote future. Reporters covering this subject are in denial about how many of their subject matter experts are full of shit, and how many times they’ve been lied to about this subject.

And the victim is the worker. It’s always the worker.