Since the beginning of 2023, big tech has spent over $814 billion in capital expenditures, with a large portion of that going towards meeting the demands of AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic.

Big tech has spent big on GPUs, power infrastructure, and data center construction, using a variety of financing methods to do so, including (but not limited to) leasing. And the way they’re going about structuring these finance deals is growing increasingly bizarre.

I’m not merely talking about Meta’s curious arrangement for its facility in Louisiana, though that certainly raised some eyebrows. Last year, Morgan Stanley published a report that claimed hyperscalers were increasingly relying on finance leases to obtain the “powered shell” of a data center, rather than the more common method of operating leases.

The key difference here is that finance leases, unlike operating leases, are effectively long-term loans where the borrower is expected to retain ownership of the asset (whether that be a GPU or a building) at the end of the contract. Traditionally, these types of arrangements have been used to finance the bits of a data center that have a comparatively limited useful life — like computer hardware, which grows obsolete with time.

The spending to date is, as I’ve written about again and again, an astronomical amount of spending considering the lack of meaningful revenue from generative AI.

Even after a year straight of manufacturing consent for Claude Code as the be-all-end-all of software development resulted in putrid results for Anthropic — $4.5 billion of revenue and $5.2 billion of losses before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization according to The Information — with (per WIRED) Claude Code only accounting for around $1.1 billion in annualized revenue in December, or around $92 million in monthly revenue.

This was in a year where Anthropic raised a total of $16.5 billion (with $13 billion of that coming in September 2025), and it’s already working on raising another $25 billion. This might be because it promised to buy $21 billion of Google TPUs from Broadcom, or because Anthropic expects AI model training costs to cost over $100 billion in the next 3 years. And it just raised another $30 billion — albeit with the caveat that some of said $30 billion came from previously-announced funding agreements with Nvidia and Microsoft, though how much remains a mystery.

According to Anthropic’s new funding announcement, Claude Code’s run rate has grown to “over $2.5 billion” as of February 12 2026 — or around $208 million. Based on literally every bit of reporting about Anthropic, costs have likely spiked along with revenue, which hit $14 billion annualized ($1.16 billion in a month) as of that date.

I have my doubts, but let’s put them aside for now.

Anthropic is also in the midst of one of the most aggressive and dishonest public relations campaigns in history. While its Chief Commercial Officer Paul Smith told CNBC that it was “focused on growing revenue” rather than “spending money,” it’s currently making massive promises — tens of billions on Google Cloud, “$50 billion in American AI infrastructure,” and $30 billion on Azure. And despite Smith saying that Anthropic was less interested in “flashy headlines,” Chief Executive Dario Amodei has said, in the last three weeks, that “almost unimaginable power is potentially imminent,” that AI could replace all software engineers in the next 6-12 months, that AI may (it’s always fucking may) cause “unusually painful disruption to jobs,” and wrote a 19,000 word essay — I guess AI is coming for my job after all! — where he repeated his noxious line that “we will likely get a century of scientific and economic progress compressed in a decade.”

Training Costs Should Be Part of AI Labs’ Gross Margins, And To Not Include Them Is Deceptive

Yet arguably the most dishonest part is this word “training.” When you read “training,” you’re meant to think “oh, it’s training for something, this is an R&D cost,” when “training LLMs” is as consistent a cost as inference (the creation of the output) or any other kind of maintenance.

While most people know about pretraining — the shoving of large amounts of data into a model (this is a simplification I realize) — in reality a lot of the current spate of models use post-training, which covers everything from small tweaks to model behavior to full-blown reinforcement learning where experts reward or punish particular responses to prompts.

To be clear, all of this is well-known and documented, but the nomenclature of “training” suggests that it might stop one day, versus the truth: training costs are increasing dramatically, and “training” covers anything from training new models to bug fixes on existing ones. And, more fundamentally, it’s an ongoing cost — something that’s an essential and unavoidable cost of doing business.

Training is, for an AI lab like OpenAI and Anthropic, as common (and necessary) a cost as those associated with creating outputs (inference), yet it’s kept entirely out of gross margins:

Anthropic has previously projected gross margins above 70% by 2027, and OpenAI has projected gross margins of at least 70% by 2029, which would put them closer to the gross margins of publicly traded software and cloud firms. But both AI developers also spend a tremendous amount on renting servers to develop new models—training costs, which don’t factor into gross margins—making it more difficult to turn a net profit than it is for traditional software firms.

This is inherently deceptive. While one would argue that R&D is not considered in gross margins, training isn’t gross margins — yet gross margins generally include the raw materials necessary to build something, and training is absolutely part of the raw costs of running an AI model. Direct labor and parts are considered part of the calculation of gross margin, and spending on training — both the data and the process of training itself — are absolutely meaningful, and to leave them out is an act of deception.

Anthropic’s 2025 gross margins were 40% — or 38% if you include free users of Claude — on inference costs of $2.7 (or $2.79) billion, with training costs of around $4.1 billion. What happens if you add training costs into the equation?

Let’s work it out!

- If Anthropic’s gross margin was 38% in 2025, that means its COGS (cost of goods sold) was $2.79 billion.

- If we add training, this brings COGS to $6.89 billion, leaving us with -$2.39 billion after $4.5 billion in revenue.

- This results in a negative 53% gross margin.

Training is not an up front cost, and considering it one only serves to help Anthropic cover for its wretched business model. Anthropic (like OpenAI) can never stop training, ever, and to pretend otherwise is misleading. This is not the cost just to “train new models” but to maintain current ones, build new products around them, and many other things that are direct, impossible-to-avoid components of COGS. They’re manufacturing costs, plain and simple.

Anthropic projects to spend $100 billion on training in the next three years, which suggests it will spend — proportional to its current costs — around $32 billion on inference in the same period, on top of $21 billion of TPU purchases, on top of $30 billion on Azure (I assume in that period?), on top of “tens of billions” on Google Cloud. When you actually add these numbers together (assuming “tens of billions” is $15 billion), that’s $200 billion.

Anthropic (per The Information’s reporting) tells investors it will make $18 billion in revenue in 2026 and $55 billion in 2027 — year-over-year increases of 400% and 305% respectively, and is already raising $25 billion after having just closed a $30bn deal. How does Anthropic pay its bills? Why does outlet after outlet print these fantastical numbers without doing the maths of “how does Anthropic actually get all this money?”

Because even with their ridiculous revenue projections, this company is still burning cash, and when you start to actually do the maths around anything in the AI industry, things become genuinely worrying.

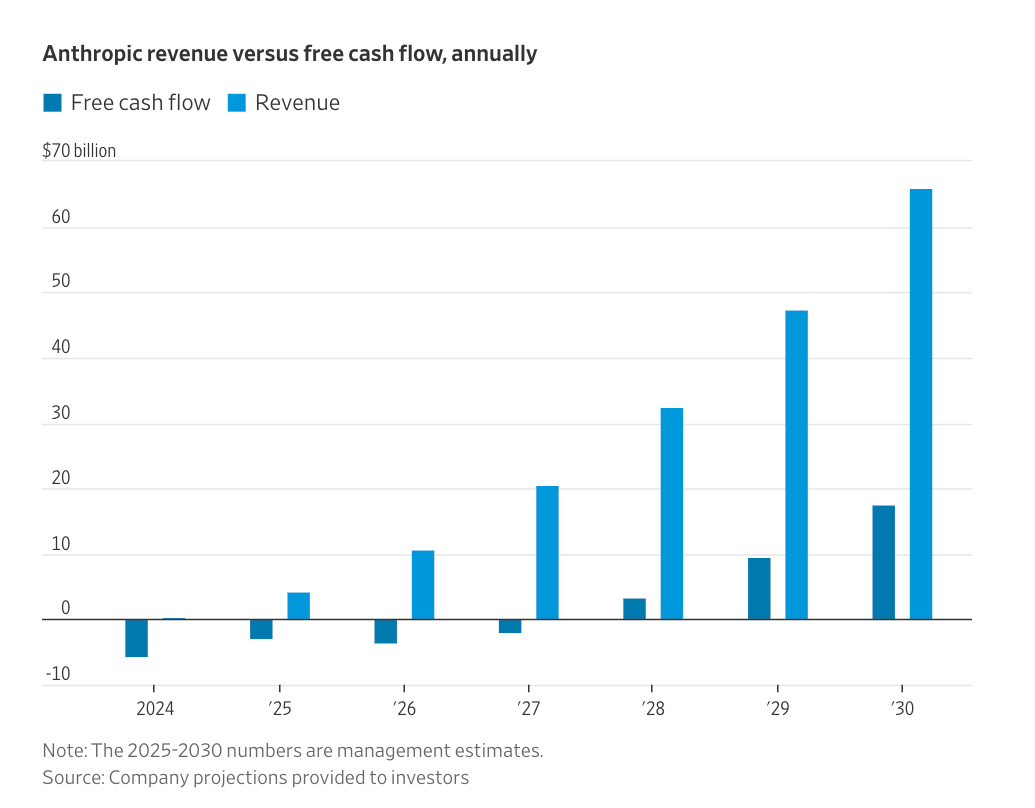

You see, every single generative AI company is unprofitable, and appears to be getting less profitable over time. Both The Information and Wall Street Journal reported the same bizarre statement in November — that Anthropic would “turn a profit more quickly than OpenAI,” with The Information saying Anthropic would be cash flow positive in 2027 and the Journal putting the date at 2028, only for The Information to report in January that 2028 was the more-realistic figure.

If you’re wondering how, the answer is “Anthropic will magically become cash flow positive in 2028”:

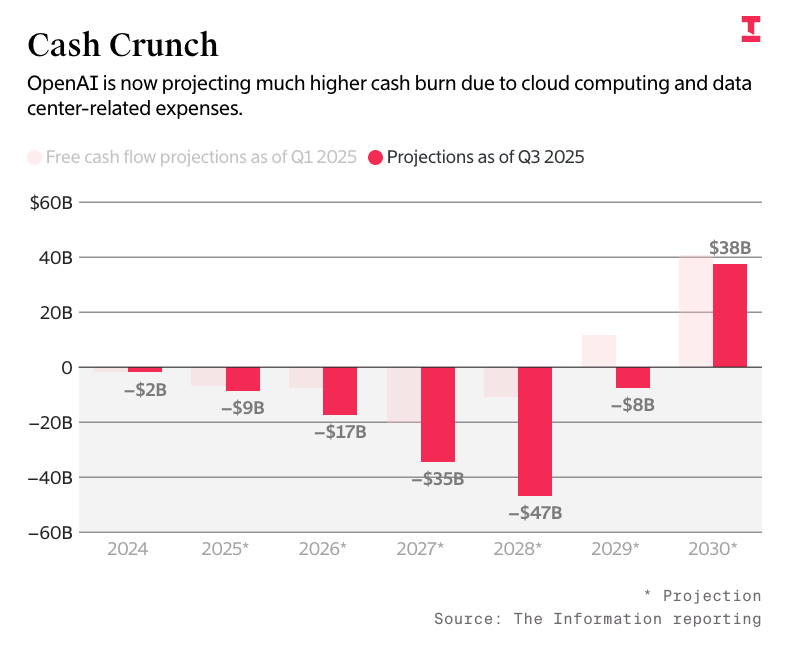

This is also the exact same logic as OpenAI, which will, per The Information in September, also, somehow, magically turn cashflow positive in 2030:

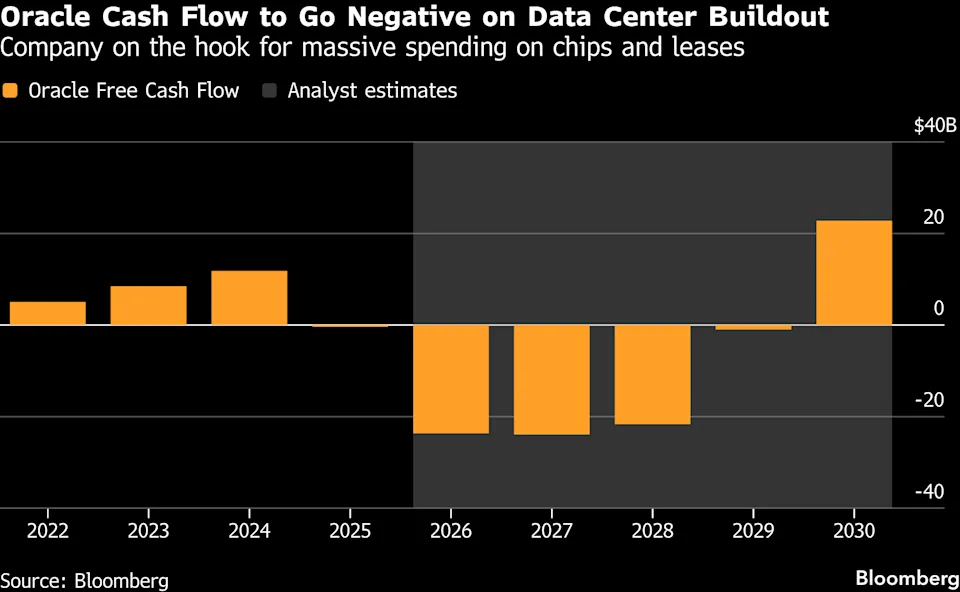

Oracle, which has a 5-year-long, $300 billion compute deal with OpenAI that it lacks the capacity to serve and that OpenAI lacks the cash to pay for, also appears to have the same magical plan to become cash flow positive in 2029:

Somehow, Oracle’s case is the most legit, in that theoretically at that time it would be done, I assume, paying the $38 billion it’s raising for Stargate Shackelford and Wisconsin, but said assumption also hinges on the idea that OpenAI finds $300 billion somehow.

it also relies upon Oracle raising more debt than it currently has — which, even before the AI hype cycle swept over the company, was a lot.

As I discussed a few weeks ago in the Hater’s Guide To Oracle, a megawatt of data center IT load generally costs (per Jerome Darling of TD Cowen) around $12-14m in construction (likely more due to skilled labor shortages, supply constraints and rising equipment prices) and $30m a megawatt in GPUs and associated hardware. In plain terms, Oracle (and its associated partners) need around $189 billion to build the 4.5GW of Stargate capacity to make the revenue from the OpenAI deal, meaning that it needs around another $100 billion once it raises $50 billion in combined debt, bonds, and printing new shares by the end of 2026.

I will admit I feel a little crazy writing this all out, because it’s somehow a fringe belief to do the very basic maths and say “hey, Oracle doesn’t have the capacity and OpenAI doesn’t have the money.” In fact, nobody seems to want to really talk about the cost of AI, because it’s much easier to say “I’m not a numbers person” or “they’ll work it out.”

This is why in today’s newsletter I am going to lay out the stark reality of the AI bubble, and debut a model I’ve created to measure the actual, real costs of an AI data center.

While my methodology is complex, my conclusions are simple: running AI data centers is, even when you remove the debt required to stand up these data centers, a mediocre business that is vulnerable to basically any change in circumstances.

Based on hours of discussions with data center professionals, analysts and economists, I have calculated that in most cases, the average AI data center has gross margins of somewhere between 30% and 40% — margins that decay rapidly for every day, week, or month that you take putting a data center into operation.

This is why Oracle has negative 100% margins on NVIDIA’s GB200 chips — because the burdensome up-front cost of building AI data centers (as GPUs, servers, and other associated) leaves you billions of dollars in the hole before you even start serving compute, after which you’re left to contend with taxes, depreciation, financing, and the cost of actually powering the hardware.

Yet things sour further when you face the actual financial realities of these deals — and the debt associated with them.

Based on my current model of the 1GW Stargate Abilene data center, Oracle likely plans to make around $11 billion in revenue a year from the 1.2GW (or around 880MW of critical IT). While that sounds good, when you add things like depreciation, electricity, colocation costs of $1 billion a year from Crusoe, opex, and the myriad of other costs, its margins sit at a stinkerific 27.2% — and that’s assuming OpenAI actually pays, on time, in a reliable way.

Things only get worse when you factor in the cost of debt. While Oracle has funded Abilene using a mixture of bonds and existing cashflow, it very clearly has yet to receive the majority of the $25 billion+ in GPUs and associated hardware (with only 96,000 GPUs “delivered”), meaning that it likely bought them out of its $18 billion bond sale from last September.

If we assume that maths, this means that Oracle is paying a little less than $963 million a year (per the terms of the bond sale) whether or not a single GPU is even turned on, leaving us with a net margin of 22.19%... and this is assuming OpenAI pays every single bill, every single time, and there are absolutely no delays.

These delays are also very, very expensive. Based on my model, if we assume that 100MW of critical IT load is operational (roughly two buildings and 100,000 GB200s) but has yet to start generating revenue, Oracle is burning, with depreciation (which starts once the chips are installed), around $4.69 million a day in cash. I have also confirmed with sources in Abilene that there is no chance that Stargate Abilene is fully operational in 2026.

In simpler terms:

- AI startups are all unprofitable, and do not appear to have a path to sustainability.

- AI data centers are being built in anticipation of demand that doesn’t exist, and will only exist if AI startups — which are all unprofitable — can afford to pay them.

- Oracle, which has committed to building 4.5GW of data centers, is burning cash every day that OpenAI takes to set up its GPUs, and when it starts making money, it does so from a starting position of billions and billions of dollars in debt.

- Margins are low throughout the entire stack of AI data center operators — from landlords like Applied Digital to compute providers like CoreWeave — thanks to the billions in debt necessary to fund both construction and IT hardware to make them run, putting both parties in a hole that can only be filled with revenues that come from either hyperscalers or AI startups.

- In a very real sense, the AI compute industry is dependent on AI “working out,” because if it doesn’t, every single one of these data centers will become a burning hole in the ground.

I will admit I’m quite disappointed that the media at large has mostly ignored this story. Limp, cautious “are we in an AI bubble?” conversations are insufficient to deal with the potential for collapse we’re facing.

Today, I’m going to dig into the reality of the costs of AI, and explain in gruesome detail exactly how easily these data centers can rapidly approach insolvency in the event that their tenants fail to pay.

The chain of pain is real:

These GPUs are purchased, for the most part, using debt provided by banks or financial institutions. While hyperscalers can and do fund GPUs using cashflow, even they have started to turn to debt.

At that point, the company that bought the GPUs sinks hundreds of millions of dollars to build a data center, and once it turns on, provides compute to a model provider, which then begins losing money selling access to those GPUs. For example, both OpenAI and Anthropic lose billions of dollars, and both rely on venture capital to fund their ability to continue paying for accessing those GPUs.

At that point, OpenAI and Anthropic offer either subscriptions — which cost far more to offer than the revenue they provide — or API access to their models on a per-million-token basis. AI startups pay to access these models to run their services, which end up costing more than the revenue they make, which means they have to raise venture capital to continue paying to access those models.

Outside of hyperscalers paying NVIDIA for GPUs out of cashflow, none of the AI industry is fueled by revenue. Every single part of the industry is fueled by some kind of subsidy.

As a result, the AI bubble is really a stress test of the global venture capital, private equity, private credit, institutional and banking system, and its willingness to fund all of this forever, because there isn't a single generative AI company that's got a path to profitability.

Today I’m going to explain how easily it breaks.